Category: General Blogs

Sunday, 18 August 2013

NHS SOS – how the NHS was betrayed book review

The book NHS SOS: how the NHS was betrayed and how we can save it is a painful story that needs reading, and acting upon.

It is the most cherished institution in the country and yet England no longer has a NHS. Getting it back is going to require effective campaigning to ensure that a future Labour Government keeps to their public promises to reverse the legislation adopted under the current Coalition Government.

The Health and Social Care Act 2012 has ended 65 years of universal health care in the form of equal access to comprehensive care irrespective of personal income. The Health Secretary has now only to promote rather than provide health care by allocating resources. Market forces and unaccountable organisations are going to be left to take over. Amongst those who hope to make a profit from the changes are 70 Mps and 142 peers who have connections with private health care firms.

Treatment on the basis of need and not the ability to pay was why the NHS was created on 5 July 1948. Before World War Two only 43% of the population were covered by the National Insurance Scheme and over twenty-one million people, mainly women, children and the sick, were not covered at all. When Churchill’s government brought all hospitals under public control, the population got a taste of universal health care that ensured it remained once hostilities ended.

In NHS SOS, a group of doctors, analysts and health campaigners uncover the lies, self-interest, democratic weaknesses and media failings that have led to the betrayal of the NHS.

Cameron and his party went to great lengths before the 2010 election to promise the electorate that the NHS was safe in his hands. Nick Clegg reaffirmed this commitment, when he joined hands with the Tories.

Within days, Andrew Lansley was unveiling his plans for radical change, none of which had been placed before the electorate, who were informed it was about putting doctors in charge. When the latter demonstrated they were bitterly opposed the public was again let down, this time by the press and TV. These institutions failed to explain this was because GP’s knew the plans involved turning the NHS into a full-blooded, competitive market open to ‘any qualified provider’ and allowing up to 49% of NHS hospitals to be used for private patients.

The BBC, which provides 70% of news consumption on TV, is slammed in the book for failing to provide an ongoing narrative of an emerging national disaster. That might have been avoided if the leadership of British Medical Association and the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges had reacted to their member’s anger by utilising it in an effective campaign.

Labour too failed to offer effective opposition in Parliament, the party that set up the NHS having helped pave the way for its destruction by favouring external competition over internal competition during the Blair and Brown years. Worse still was the paying of capital development projects through the woefully inefficient and horrendously expensive Private Finance Initiative. Unite the union wants to see more working class people elected as Labour MPs and this books shows just why.

What you can do to the save the NHS is the title of last chapter of the book. Union members can join established campaigning organisations such as Keep Our NHS Public. If there isn’t a local campaign then consider setting one up. Help mobilise public opinion with events, petitions, marches and other protests. Unite is also seeking reports of cuts and closures. In the lead up to the next election pressurise prospective candidates on their views about repealing the 2012 Act.

NHS SOS: How the NHS was betrayed – and how we can save it is published by ONEWORLD and costs £8.99

Monday, 22 July 2013

BEYOND PULDITCH GATES book review

Published in 2001 by Wolfhound Press

Henry Hudson

There are too few novels on work that are written by working class people. Henry Hudson was from 1969 to 1999 a worker in Dublin’s power industry. The Transport and General Workers Union member used his experiences to good effect in an amusing, occasionally hilarious, book that is based around three decades of construction worker Timmy Talbot’s life from the late 50s onwards.

Pulditch Gates power station is a bleak place made bearable by the comaraderie amongst those who work there. Each day is a constant battle of wits between the men and management. Amongst the latter is the husband of the daughter of one of Ireland’s richest men and who in addition to having unsuccessfully tried to force himself on Talbot’s wife, Patsy, has also left her former friend pregnant and imprisoned in a convent for ‘wayward women.’

When a mix-up ensures Talbot and his mates end up getting permanent jobs they use their good fortune to collectively organise for better pay and conditions. But, as Ireland’s economy hits rock bottom they find themselves chucked in jail for threatening electricity supplies. The court rooms scenes in which they are sent down, their imprisonment and their release under a shoddy, compromise deal are amongst the best bits in the book and are highly amusing.

Other scenes will also hit a chord with Irish workers who can recall the 60s and 70s when management’s ‘right to manage’ and a lack of abortion rights were challenged. Hudson’s novel thus celebrates the lives of those men and women who challenged poverty, ignorance and fear.

Alex Nunns the Candidate – Jeremy Corbyn’s Improbable Path to Power

(OR Books, £15 – reviewed in 2016)

A book that skilfully analyses the political motives and organisational forces behind the election as Labour leader in September 2015 of Jeremy Corbyn, who – as Alex Nunns points out on page 294 – “was in no sense ready for it” and “was thrust into a nearly impossible situation”.

The jury is still, of course, still out on Corbyn as a Labour leader.

But what this book does clearly show is that those who stood against him – and their supporters – had nothing to recommend them as none could envisage an economic alternative to the Tories austerity package that has cut the standard of living for many, whilst also failing to reduce Britain’s economic debt.

Corbyn has been an MP since 1983. He held no government post during the period when Labour was in office between 1997 and 2010. The Islington MP had, though, built a reservoir of personal support amongst radical campaigning organisations (many not directly connected to Labour) by backing their causes in and out of Parliament. These causes included his steadfast opposition to the disastrous Iraq War.

Meanwhile, having seen the selection of Labour Parliamentary candidates become dominated by Tony Blair’s New Labour, unions – particularly UNITE and the GMB – began to get organised at the start of the current decade to try and get pro-union candidates, preferably working class ones, into Labour seats.

In 2010, the new Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition Government chose to use the 2008 financial crash to impose severe public sector cuts particularly on the poorest in society such as the unemployed, disabled and sick. Privatising the NHS was expanded. When opposition to such moves was led by the trade unions and community groups, New Labour MPs preferred to look the other way whilst Corbyn and his closest ally, John McDonnell MP, rallied to the fightback against austerity.

Nevertheless, the chances of Corbyn ending up as Labour leader were remote to say the very least. However, New Labour in 2014 had over extended itself. In its drive to maintain the power of the Parliamentary Labour Party – and weaken the trade union influence – New Labour backed Miliband’s decision to implement the Collins Review recommendations, whereby the next Labour leader would be elected on a one-member-one-vote system. John Rentoul, a Blairite journalist proclaimed: “it means that the next Labour leader will be a Blairite”.

Rentoul’s contention was to be tested when Miliband quit as leader following Labour’s poor showing at the 2015 General Election. At the start it seemed highly unlikely that Corbyn would even get on the ballot paper as he required a minimum of 35 nominations from MPs. It helped that despite his political differences with most of his Parliamentary colleagues he had never resorted to personal attacks on them. There was also a feeling that all sectors of the Party should be represented. Although he had less than 20 MPs who intended actually voting for him it proved possible to gather in sufficient nominations for Corbyn to be able to stand against Liz Kendall, Andy Burnham and Yvette Cooper. Burnham was the bookies favourite, Corbyn was 200-1.

Initially the aim of those backing Corbyn was for him to enjoy a respectable showing and move the debate to the left. But it soon became apparent that there was a groundswell of support for Corbyn amongst all sections of the Labour Party. These included many who had been in it for years, those who had joined as a result of Ed Miliband’s opposition – timid as it was on too many occasions – to austerity and those, many from the campaigns and organisations he had worked with for decades, who were being persuaded to join Labour in order to elect Jeremy Corbyn as its leader. Throw in the work undertaken by the trade unions to recover the party for the working class then all told this was a powerful combination.

It was, though, one that needed organising and co-ordinating. The book is extremely good in charting the achievements of such as Alex Halligan of Unite in organising events at which Corbyn could speak directly to potential supporters and also help him reach out to a larger audience using social media.

Corbyn, of course, won by a landslide and captured every section – the older, relatively new and the brand new – of the Labour Party. He beat all his opponents by obtaining a majority at the first ballot.

Since then Jeremy Corbyn has had to face down a series of revolts amongst his Parliamentary colleagues. There has also been an unprecedented level of media hostility – much of it very personal – even though as the Labour leader admits in this book his economic programme would not be seen as particularly remarkable in Germany.

Whether, of course, the move to the left in Labour that Jeremy Corbyn has helped inspire can be maintained and built upon to secure a more equal society for everyone is still up for grabs. That’s up to all of us and not just Jeremy Corbyn!

The Life and Times of James Connolly

C. Desmond Greaves

This book, first published in 1961, is rightly regarded as the definitive biography of Ireland’s greatest labour leader. Author C. Desmond Greaves skilfully combined academic research with interviews with Connolly’s surviving associates to produce the story of James Connolly’s political life and public activity. This ended when, unable to walk after being shot in the leg during the failed Easter Uprising in Dublin in 1916, he was executed by a British firing squad on Friday 12 May 1916. His execution, and those of fifteen others, was to shock the labour movement across the world. In Ireland the subsequent public revulsion at the deaths turned those who had taken up arms into heroes amongst the large mass of the people.

Connolly was born to Irish parents in Edinburgh on 5 June 1868. His father, John, was an unskilled labourer and mother Mary a domestic servant. The family lived in abject poverty within the Irish colony in the city and James started work at the age of ten or eleven. By fourteen he was already politically conscious with a keen interest in the Land League, which aimed at restricting the privileges under British rule of landlords in Ireland.

A lack of a regular income saw James follow his older brother John into the British Army. He joined the King’s Liverpool Regiment, which counted as an Irish one as its uniform was dark green. It was as a raw militiaman that Connolly first saw Ireland in 1882. He was to remain seven years and his time there coincided with the most progressive phases of the land agitation actions, including the use of boycott tactics by local people against landlords who threatened to evict their tenants.

When Connolly arrived back in Scotland he married Lillie Reynolds, a Protestant, on 13 April 1889 and the pair settled in Edinburgh at a time when Britain’s status as the workshop of the world began to come under threat from its international competitors. An industrial depression ensued, but the ‘new unionism’ that followed successful strikes by unskilled workers, such as the dockers in London in 1889, saw the labour movement grow immeasurably. (1)

Socialism was also winning converts. Connolly, who became a temporary worker at the Edinburgh Corporation Cleansing Department, joined the Socialist League, which was a breakaway from the Social-Democratic Federation. Both were loose informal unions of quasi-independent socialist clubs. Many people held joint membership and both organisations stood for the complete separation of Ireland from Britain.

Connolly took up the challenge of studying socialism by attending meetings and reading extensively. He began writing and undertook an apprenticeship in public speaking. His regular spells out of work forced him to try and find alternative employment. However, attempts to found a small shop and later become a cobbler proved unsuccessful. Meanwhile, he increasingly began to stand as a socialist candidate in local elections before taking up full-time work as a political propagandist/organiser. When this failed to regularly pay the bills of his expanding family, Connolly was glad to accept the invitation by the Dublin Socialist Club to become its paid organiser in 1896.

Connolly helped found the Irish Socialist Republican Party, which was based upon the public ownership by the Irish people of the land and instruments of production, distribution and exchange. The party’s manifesto had socialism as its objective and included abolition of private banks and universal suffrage. Connolly had combined his belief in Irish independence with a programme for working class rule. The rest of his life – with all its twists and turns and increasing political maturity that saw him abandon syndicalism – was to be dedicated to these two aims, which he saw as inseparable.

Whilst he supported the movement for Irish Home Rule, which sought to reduce the UK’s political control over Ireland, he stated: “If you remove the English army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organisation of the Socialist Republic your efforts would be in vain. England would still rule you. She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and individualist institutions she has planted in this country and watered with the tears of our mothers and the blood of our martyrs”.

In 1903, Connolly, following a successful tour there the previous year, emigrated to the United States, where he again found it difficult to find work. He joined Daniel De Leon’s Socialist Labor Party and became one of the founders of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which sought to bring about revolution by creating one great union combining all trades in one organisation.

Connolly became an IWW organiser, being able for the first time to devote his energies to work he passionately believed in. He was a tour de force organising tramwaymen, dockers, garment workers and many more. Successful strikes were organised.Yet by 1908, Connolly, boosted by James Larkin’s successful uniting of Catholics and Protestants during the transport strike in Belfast the previous year, was keen to return to Ireland. He did so in 1910 and in Dublin he proposed the establishment of an Irish Labour Party including the trade unions.

Socialist ideas were to grow rapidly in Ireland in 1909-10. Two of Connolly’s new works Labour, Nationality and Religion and Labour in Irish History were well received. Connolly joined the Irish Transport Workers’ Union (ITWU) in Belfast and with seamen and dockers in revolt over their pay and conditions he became Belfast organiser of the Union.

Connolly sought to unite Protestants and Catholics, doing so successfully amongst mill-girls in the autumn of 1911. He was though unable to prevent Sir Edward Carson’s appeal to the vast majority of the Protestant working class to oppose, if need be by military means, the Home Rule Bill that was then making its way under the Liberal Government of Herbert Asquith through the House of Commons. Carson, the former-solicitor General and leader of the Irish Unionist Alliance and Ulster unionist Party between 1910 and 1921, demanded that the nine county province of Ulster in the north of Ireland be excluded from the Bill.

In 1913, Connolly played a major role in the great Dublin lock-out that commenced when owner William Murphy informed his employees at the Dublin Tramway Company that they must quit the ITWU or lose their jobs. The struggle, at the end of which virtually the whole of the working class in Dublin was engaged, is, like throughout all this book, graphically detailed by the author, who, in addition, provides an understanding of the main characters and organisations and the political and economic forces they represented.

The heroic resistance in 1913, during which was developed the Irish Citizen Army to defend strikers against the police-protected armed strike breakers, was to last eight months. It was broken when, due to starvation, the tramway workers returned to work. They were also forced to sign the Murphy Pledge but they retained their union membership and paid their fees openly. No workers were sacked and because of the solidarity actions of their own workers then many of the weaker employers were at the brink of bankruptcy and did not dare repeat the challenge to an undefeated labour movement. The battle had been drawn.

Later in 1914, the tensions between the major imperialists over who should have control of resources in Africa, where between 1870 and 1914 the percentage of the continent directly controlled by the European imperial powers had risen from 10 to 90 per cent, finally burst and World War I commenced. From all parts of Ireland many joined up to fight for Britain. Connolly was never going to do so stating: ”For the sake of a few paltry shillings, Irish workers have sold their country in the hour of their country’s greatest need and greatest hope”. He declared: “We have no foreign enemy except the Government of England…We serve neither King nor Kaiser, but Ireland”. The road to the Easter Uprising was set.

On 18 July 1915, Connolly held a massive anti-conscription meeting in Dublin and warned that there would be attempts to introduce conscription although, in fact, the campaign he organised against it meant the Government held back any plans they may have had.

Connolly then began dreaming of a plan of action that would see the Citizen Army, whose discipline was tightened up for the military conflict ahead, start the uprising against British rule and be backed by the much larger Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), which unbeknown to Connolly was planning its own uprising. The IRB, which was dedicated to establishing an ‘independent democratic republic’, was founded in 1858 and its counterpart in the USA was known as the Fenian Brotherhood. Subsequently, members of both wings became referred as ‘Fenians’.

Meanwhile, Connolly kept up a constant barrage against the World War, its savagery and its political and economic consequences. Trade union branches were established in many industries, bringing him into conflict with others that sought Irish independence but not with the working class in control afterwards.

On 16 April 1916, Connolly said: “The Irish working class is the only secure foundation upon which a free nation can be reared”.

Discussions that took place in January 1916 between the IRB and Connolly established the date when the Uprising would take place. The former was, though, split with Eion MacNeill, who in 1913 had formed the Irish Volunteers, which included the IRB, opposed to an armed uprising as he believed there was little chance of success in an open conflict with the British Army.

When MacNeill learned of the imminent revolt he used every means, except informing the authorities, to get people not to participate. It meant that when the Uprising began on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, the numbers on the IRB side, led by Patrick Pearse, were considerably reduced down to around 700 with just 120 Citizen Army men. Connolly knew there was no chance of success especially as plans by (Sir) Roger Casement to land a shipment of German arms in County Kerry had gone badly wrong.

The rising saw key Dublin locations seized and an Irish Republic proclaimed. The British Army then brought in thousands of armed reinforcements plus artillery and a gunboat. The rebels were gradually surrounded and bombarded with artillery and on 29 April, Pearse agreed to an unconditional surrender. Almost 500 were killed in the Uprising. Most were civilians who died as a result of British military actions, which included heavy shelling that left many parts of inner city Dublin in ruins.

A total of 3,430 men and 79 women were arrested in the aftermath of the failed uprising. Most were subsequently released without charge. 90 people though were sentenced to death and fifteen were executed at Kilmainham Gaol by firing squad between 3 and 12 May.

Connolly, unable to walk because of a shattered ankle, was tied to a chair before being the last to be shot. His death was celebrated by a gleeful William Murphy.

However, the executions, combined with news of the subsequent atrocities that were carried out by the British military in the aftermath of the Uprising, was to cause general outrage amongst a significant section of even the Irish public that had not supported Connolly and Pearse. Backing was to swing towards support for the Irish rebels of 1916.

Desmond Greaves shows how most socialists internationally struggled to comprehend why Connolly had helped lead an Uprising against British rule in Ireland, especially one that was doomed when it started. Some even belittled Connolly’s actions.

Russian revolutionary, Vladimir Lenin, who was to lead two successful revolutions within the following eighteen months, was one of those who did understand why Connolly had moved, stating, “Whoever expects a ‘pure’ social revolution will never live to see it…the misfortune of the Irish was that they rose prematurely, when the European revolt of the proletariat had not yet matured”.

The book ends with an epilogue in which the author declares that: “James Connolly was one of the first working-class intellectuals. He was one of the most tireless and dedicated socialist workers who lived”.

- THE GREAT DOCK STRIKE OF 1889 by Unite Education https://markwrite.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/the-great-dock-strike-of-1889-web-booklet11-23272.pdf

Note on women’s contribution to the Easter Uprising.

One weakness of Desmond Greaves work is the absence of the history of women’s contribution to the Easter Uprising. Now, as part of the centenary celebrations, Dublin City Council has published a book detailing 77 of the women who participated, totalling an estimated 280.

They include Constance Markiewicz – who later became the first women to be elected to (the British) Parliament – who was married to a Polish count and advised women to “buy a revolver”.

Annie Norgrove was a 17-year-old Protestant. Her gas-fitter father was an active trade unionist. She joined the Irish Citizen Army during the 1913 Lock-Out and spent the days of the Rising avoiding sniper fire to ferry water to the insurgents.

Richmond Barracks 1916 We Were There – Women of the Easter Uprising by Mary McAuliffe and Liz Gillis, Dublin City Council, 2016.

FROM BENDED KNEE TO A NEW REPUBLIC: How the Fight for Water is Changing Ireland

The Liffey Press

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Bended-Knee-New-Republic-Changing/dp/1908308958

This is a very easy to read, highly informative book by Brendan Ogle, the Unite education, politics and development organiser for Ireland.

The Right2Water and Right2Change campaigns have proven — thanks to a unique blend of community, trade union and political activism — to be massive successes. Ogle has played a major role and in this book he explains why the campaigns — which started in 2014 and are ongoing — are necessary and how they have changed the face of politics in Ireland, hopefully for good.

The people of the Irish Republic have been forced to endure austerity for many years. The Right2Water campaign began after the painful journey, backed by the EU, towards water privatisation started when water meters began to be installed by Irish Water. The Irish Government had created this company in 2013 with the aim of getting Irish citizens to now pay privately for their water rather than had previously been the case collectively through their taxes.

Ogle begins by making a very powerful case as to why the Right2Water campaign could easily have been one for either health or housing, areas where the private sector has been politically allowed to dominate the public sector with disastrous consequences for working people.

The author then shows how the supply of water is being privatised right across the globe. This includes the UK where water companies have upped prices and are now enjoying massive profits and yet pay hardly any tax and are also putting little investment into the infrastructure needed to supply water to customers. Ogle shows how international companies are seeking new water avenues to explore, thus making the future even more worrying.

The Irish Republic has largely been dominated politically by centrist parties such as Fine Gael and Fianna Fail. Corruption has flourished. Trade unionists and (some) socialists who longed for a better future have tended to look towards the Irish Labour Party, but like in Britain it has become increasingly social democratic rather democratic socialist, more Blair than Attlee.

Ogle deconstructs the Irish Labour Party, showing how its politics are the mirror image of New Labour whereby neoliberalism and globalisation is good even if it wrecks working-class communities. As such Irish Labour, with 37 seats, was content to enter into a coalition government with Fine Gael in 2011. The party did its best to undermine the two campaigns and was to lose heavily at the General Election in 2016 and was reduced to just 7 seats.

With virtually all of the mainstream media either hostile or uninterested in the ever increasing numbers of people getting involved in the Right2Water campaign, Ogle shows how social media can be very important in reaching out and bringing on board all sectors of the community.

When large scale mobilisations meant they could no longer ignore what was happening, the Irish State and its mainstream politicians then attempted to portray the developing movement as a threat to the State. This was despite the fact that all the protests, many of which have been massive, had, with some small exceptions, been peaceful ones.

Ogle bemoans the lack of an impartial and informed media in Ireland and also the lack of a functioning democracy such that there is no right to recall MPs when they fail to carry out promises they have made during General Elections. One of the great parts of the book is that it shows how the campaign in Ireland has linked up with similar water campaigns right across the world and particularly those in Detroit in the USA and in Greece.

The book shows how Unite, in particular, and some sections of the trade union movement have been at the forefront of the fight against water privatisation.

The book describes how Unite, working with Trademark Belfast, has provided political economy courses for non-aligned community activists. This has given the water protest movement access to the type of information that would enable them to understand the political and economic agenda behind water privatisation.

In 2015, the Right2Water campaign undertook a period of reflection and analysis and this led to the development of a more ambitious platform called Right2Change. Ten policies, all of which were only agreed after extensive debate in which political parties, trade unions and community activists were represented — are listed. They are: a right to water, jobs, housing, health, education, democratic reform, debt justice, equality, a sustainable environment and a fair economy. With 37 per cent of its citizens suffering deprivation, an unemployment rate of over ten power cent and thousands driven abroad they were all necessary.

To prove the ten points are also affordable, Right2Change provided a rigorous, detailed economic explanation of where funds can be founded in a country where major multinational companies such as Apple pay a fraction of their huge profits in tax.

Right2Change then sought to get political parties to agree to back these policies at the 2016 February General Election. In constituencies where candidates refused, attempts were made to get community activists who did back the policies to stand for office. 106 election candidates endorsed Right2Change. None were from the Labour Party.

Almost 100 of the 158 seats were won by candidates who had campaigned on an anti-water charges platform. For the first time ever in modern Irish politics a majority Government could not be formed. The key outgoing government initiative of wanting to cut taxation was rejected by voters more concerned with the state of essential public services.

Fine Gael is now the senior partner in a coalition government that is supported by Fianna Fail, who have promised not to bring the government down in confidence motions or object to reshuffles.

Water charges have been suspended until the end of 2016 and the government has also set up a hand-picked ‘independent commission,’ which is excluded from assessing the social impact in relation to how Ireland provides water to its citizens. Yet even this was insufficient for the European Commission as just four days after the UK voted to leave the EU a spokesman for the Commission confirmed that Ireland would be fined if domestic water charges were not reinstated. Such an ill-judged and ludicrous statement — in a country that has 1 per cent of the EU’s population and has been saddled with 41 per cent of its banking debate — must inevitably make an Irish exit from the EU more likely in the future. Ogle questions ‘whether the relationship that Ireland has with the EU as currently structured can be sustained.’

Right2Water has made a lengthy submission to the Water Commission calling for water meters to be scrapped, water to again become paid for through general taxes and how water charges infringe human rights. It wants the Dail (Irish Parliament) to abolish domestic water charges.

A decision must be made shortly. Meanwhile Ogle isn’t sitting back waiting and ends his book asking ‘So Where Will Our Progressive Government Come From?’ and like everything else in this excellent book the author offers some great analysis and ideas that have wide international significance.

UNTIL THE CURTAIN FALLS: No Pasaran

David Ebsworth

This is the exciting sequel to Ebsworth’s highly enjoyable first novel – The Assassin’s Mark – on the 1936-39 Spanish Civil War.

Peace-loving, naive left-wing journalist, Jack Telford, had, during a two-week spell as a Foreign Correspondent in September 1938, surprisingly become fond of many of his fellow travellers on a bus tour of battlefield sites organised by General Franco’s Tourism Department.

The democratically elected Republican government was battling to prevent Franco, backed by fascist forces from Italy and Germany, from establishing a Nationalist government. The tours were intended to get international tourists to help celebrate Franco’s successes and get them to return home and ‘spread the word.’

Telford is drawn to a journalist who holds of one of Franco’s most coveted awards. He’s shocked to discover she is, in fact, a passionate communist with links to the Soviet Union, who intends to use her access to the general to assassinate the dictator. Problem is the plan if successful would have left Jack to take the blame and so he kills the woman.

But what next? Can he escape being killed by a growing band of people and organisations? They include the Soviets that are providing military assistance to the Republican government and Franco’s forces. There are also pro-fascist members of the British diplomatic core who learn that Telford knows they are doctoring reports being sent home about the true extent of war materials going from British firms in Spain to Hitler from the nationalists.

Ebsworth – who in real life is former TGWU regional secretary Dave McCall – has really done his research. In Until the Curtain Falls, Ebsworth brings to life the carnage, atmosphere, heroism, love, people, politics, architecture and landscape of Spain in the months leading up to the eventual defeat of the Republican government in 1939.

The tale is a great story that is packed with moments of real drama and passions. The survival of Telford – plus those helping him – is constantly thrown into doubt as he and his pursuers battle to outwit one another. Ebsworth, for whom this is his sixth book, is deservedly building a reputation for writing entertaining novels and this latest work will add to that reputation.

The Assassin’s Mark was the Unite book of the month for November 2013: http://www.unitetheunion.org/growing-our-union/education/bookofthemonth/november/#sthash.xEvaJgkp.dpuf

The book costs £10.99 and can be ordered through David’s site at:- http://www.davidebsworth.com/until-curtain-falls

ISBN 978-1-78132-643-5

WORKING THE LAND: A history of the Farmworker in England from 1850 to the Present Day

Nicola Verdon

This is the most comprehensive account so far written of the history of agricultural workers since the 1850s, when farmworkers, at the height of the industrial revolution, were still numerically the biggest group of workers in England. Today, with under 100,000 in total, farmworkers account for under 1% of the employment totals. Many of their roles though remain essential.

Dr Nicola Verdon is a history lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University. Her previous book, published in 2002, was on Rural Women Workers in Nineteenth-Century England. This showed the vital role women, often overlooked, played in the many developments in farming through the nineteenth and into the twentieth century. Her findings have been used to contribute to radio and TV programmes. Sadly, the book was only made available to an academic audience.

Verdon hopes — and is pushing to make — her second book more widely available via ebook and paperback. She would welcome opportunities to address trade union and labour movement gatherings about its contents. Unite branches can contact Nicola to discuss how to organise a visit by her to their meetings. It should prove a fascinating event as she certainly knows her subject.

An economic explanation of the forces shaping the countryside is combined by Verdon in Working the Land with the history of rural labour markets, employment pattens, the farm workforce and rural households and daily family life.

The author grew up in the countryside and has dedicated the book to her grandfather whose employment trajectory is typical of many agricultural workers. Born in a small Derbyshire village he was part of a large family and he left school soon after becoming a teenager to become a farmworker on a number of farms over the following years. He then went to live on a Nottinghamshire farm before quitting the sector to become a lorry driver and earn considerably more than in his previous jobs.

Verdon’s grandfather was one of a number of former agricultural workers interviewed. Getting today’s farmworkers to speak openly about their experiences is difficult. “They are reluctant to talk. Farmers are also wary if someone wants to speak to their employees, who in engaging with a researcher would reveal they are thinking about pay and conditions. Farmworkers worry this would lead to a loss in employment and so, like in previous generations, it is better to remain silent.” Verdon has found it especially difficult to make contact with migrant workers, the most exploited section of farmworkers today.

In order to overcome some of the silence, Verdon has also for two decades plus ploughed through official and Parliamentary papers and has sought, I believe successfully, to capture the thoughts of farmworkers, male and female, about their work.

There are a number of things in the book that would shock many members of the public that surveys show know very little about how much of their food is produced on a farm.

The first is the high skill levels of many farmworkers since 1850 onwards. Whether it is working with horses or a sheep dog, ploughing a field to driving — and often fixing — heavy vehicles and harvesters it is apparent that many tasks require a real talent and ingenuity. That includes making an objective assessment of whether weather conditions might rule out particular tasks at certain times.

“Many people think that farmworkers have and are badly paid because they are not skilled, but that is simply not so,” said Verdon.

The relatively high numbers of female farmworkers is also revealed in Verdon’s book. “There is a misconception that agriculture is only masculine. I wanted a front cover that included men and women as the latter need to be fully recognised,” said Verdon who also explained that it was a popular myth that the Women’s Land Army had been significant in improving farming outputs during WWI. “Really it was those that always worked on farms, combined with an input from local men and women, that helped ensure our survival at the time. “

What WWI – and later WWII – did do was bring about a general recognition that the products being produced by farmers and their employees was essential for life. There was a genuine optimism that things would change for the better after the 1917 Corn Production Act introduced the first minimum wage for agricultural workers. The retiring Tory Government knocked it out of existence but once the first ever Labour Government re-introduced it in 1922 it was here to stay until the more modern Tories, combined with their Lib Dem friends, scrapped it in England at the start of this decade.

Guaranteeing better wages and conditions helped farmworkers with their drive to produce quality food but the numbers doing so continued to fall. The Labour Government after WWII maintained guaranteed prices for farming products. Generous grants for farm equipment — especially tractors — led to a continuing fall in employment totals.

Some farmworkers left the industry reluctantly but others welcomed the opportunity to take up jobs with better pay and less hours needed to earn it. Verdon admits that she did not want the book to become — as it could have — very depressing. “Many of those who left, either voluntarily or forcibly, the land have done well.”

What is undoubtedly depressing is that farmworkers still need to be better organised and represented. “The ending of the AWB in England under the basis that farmworkers are covered under minimum wage legislation was viewed by many of the farmworkers I interviewed, even those paid more than the AWB rates, with disquiet. They understand that the legislation provided a framework for all round better conditions and they worry that there will be, like after legislation was scrapped after WWI, wage deflation amongst groups of highly skilled farmworkers. They are right to be concerned,” said Verdon.

At this point it would be great to report that farmers – and politicians who they work closely with – really care about those farmworkers, of all nationalities, who play such a vital role in helping feed all of us. Verdon was the guest speaker recently at The Farmers Club in Whitehall. Tory MPs were present. Verdon found that there was a real interest in farming policy but hardly any concern about workers except for the need to ensure a plentiful supply of cheap migrant workers in the future. Nothing changes.

Interviewing Verdon then it is clear that she shares a passion for the history of landworkers and how this might aid their current struggles. “I look forward to being contacted by readers to discuss me speaking at their trade union branch meetings. I am also pushing the publishers to bring down the cost of my work so that is available in paperback,” said Nicola.

To contact Nicola send an email to n.verdon@shu.ac.uk or ring 07402 867472

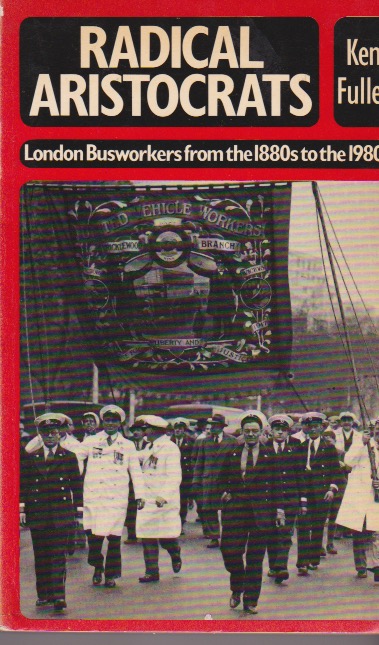

- Radical Aristocrats: London Busworkers from the 1880s to the 1980s

- From Bended Knee to a New Republic: How the Fight for Water is Changing Ireland

- Beyond Pulditch Gates – a novel on the building industry in Ireland

- Blacklisted – the Secret War between Big Business and Union Activists

Author Q&A : Dave Smith - Images Of The Past : The Miners’ Strike by Martin Jenkinson, Mark Harvey and Mark Metcalf

- The 1913 China Clay Strike by Nigel Costley

- the British Strike – Its Background, Its Lessons by William F Dunne

- The Dignity of Chartism by Dorothy Thompson, review by Tony Shaw

- the Labour International Handbook, edited by R Palme Dutt (1921)

- Mick Jenkins the General Strike of 1842

Click here to read the whole book….

11. Bradford Trades Council centenary-year brochure

SHARE THIS:

RADICAL ARISTOCRATS: London Busworkers from the 1880s to the 1980s

Ken Fuller

Lawrence and Wishart 1985

This is a detailed account of how the combination of mass car-ownership and right-wing leadership within the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU), which purged radicals, left London bus workers, once the aristocrats of the working class, unable to effectively combat an employer-led and government backed offensive on their wages and conditions.

It was written in 1985 by Ken Fuller, a former bus driver who by then was a full-time official in the TGWU bus section. Fuller’s initial study began as a lay rep on the TGWU District Learning Course. This book therefore stands as an important testimony to the importance of trade union education in general and to Fuller himself who sought in the book to rouse busworkers to fight plans by the then Tory Government of Margaret Thatcher to deregulate the buses. Sadly, it was a struggle the Tories were to go on and win and following which the decline in London bus workers wages and conditions has continued ever since.

———————————————————————————————————–

It was in 1888-1889 (see The Great Dock Strike of 1889: http://www.unitetheunion.org/growing-our-union/education/bookofthemonth/july-2015/ ) that unskilled and semi-skilled workers began organising within trade unions to fight for better terms and conditions.

In 1889, barrister Thomas Sutherst successfully organised over two thousand London tram men and some from the omnibuses into their first trade union. The men were amongst the highest-paid sections of the working class but only because they worked a 15-16 hour day, seven days a week. The union organised a strike that briefly reduced the number of hours worked but, largely as a result of an individualist attitude outlook amongst its members, it failed to last long.

The replacement of the horse-drawn omnibus by motor buses in the early years of the twentieth century required a more skilled workforce that brought with it a greater measure of self-esteem and professional pride.

New unions had continued to be formed in the new century. Many were influenced and led by socialists such as Tom Mann. https://markwrite.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/the-great-dock-strike-of-1889-web-booklet11-23272.pdf London dockers struck in 1911 and a million miners were out the following year. In 1913 the newly formed London and Provincial Union of Licensed Vehicle Workers (LPU) had recruited three-quarters of the 12,000 busworkers in its area. By adopting an anti-capitalist position that included opposing both WWI and the attempts of their employer to attack their terms and conditions it went on to become a militant, highly politicised trade union over the next five years

By 1919 London busworkers were paid more and worked less hours than most other semi-skilled workers. As an organised group they had achieved, writes Fuller ‘an aristocratic status and a strong political identity virtually simultaneously.’

This situation was to come under pressure when — in the understandable drive for a national organisation for all passenger transport workers — the LPU amalgamated with the more moderate Tramway and Vehicle Workers. This led to the formation in 1920 of the United Vehicle Workers, (UVW). This started life with 109,245 members with bus workers outnumbered by tram and lorry men.

The new union was to be short lived when in 1921 its members, particularly the tramworkers, voted to become part of Ernest Bevin’s one large transport union, the TGWU, which brought together 18 unions with a grand total of 362,000 members.

Not everyone within the UVW was convinced of Bevin’s leadership skills. The UVW organiser George Sanders was a lifelong socialist with a strong London busworkers following. Sanders later played a major role in the British Bureau of the Red International of Labour Unions, which was formed to co-ordinate Communist activities within the trade unions.

Sanders criticised Bevin for attending a secret dinner with business leaders. The knees-up was designed to create a better understanding between capital and labour in order to help advance British world trade. Dissatisfaction with Bevin was to quickly increase when — unlike in the tram section of the new union — when the TGWU leader refused, during a time when their employer had the money to pay up, to lead struggles to secure improvements in busworkers pay and conditions.

The outcome was the development of an effective unofficial Rank and File Movement. (R&FM) According to Fuller this arose ‘largely out of Communist initiatives and was led by Communists.’

Busworkers meanwhile demonstrated a willingness to fight for their class when called upon. They responded magnificently to calls to participate in the 1926 General Strike and when it was called off by the TUC General Council many were unhappy at the miners’ being left to, ultimately unsuccessfully, battle on alone.

The R&FM subsequently grew on the buses. This resulted in a struggle to up pay — largely successful after previously imposed wage cuts were restored by the newly formed London Passenger Transport Board in January 1934 – and over speed ups that had cut travel time between stops. Some drivers had even found themselves being fined for exceeding the speed limit as they battled to keep to the schedule. There was also frustration at the unwillingness of the TGWU to lead a struggle to win a seven-hour day.

Meanwhile an attempt to forge unity with unofficial movements amongst tram and trolley bus workers was unsuccessful. It was this that ultimately paved the way for Bevin to defeat the radicals on London’s buses.

Busworkers began strike action in support of their claim for a seven-hour day on 1 May 1937. With the Underground, trams and trolleys all working normally there was little disruption. This continued to be the case until busworkers were instructed on 28 May by their union to return to work. A dispirited R&FM conference was unable to organise any resistance. Some minor concessions were made by their employer. In the aftermath, Bevin moved quickly to expel and disbar from TGWU membership many of the R&FM leadership.

An unprecedented struggle for rank and file control, which had been made possible because of centralised control of the buses across London, of the TGWU’s affairs was now at an end. It was only to be partially reversed when Frank Cousins became elected to the post of General Secretary in May 1956.

By then London busworkers, who also lost badly again when they took strike action over pay in 1958, had lost their claim to aristocratic status as their industry lost out to a post war capitalist society based on mass-consumption in which one of the most important components was car-ownership. The Tory government that held office between 1951 and 1964 encouraged road-building for private cars at the expense of public transport. This included the railways which were cut massively by Dr Beeching in 1963. Passenger demand on bus and trains plummeted.

London Transport (LT) took full advantage to restrict advances in pay even though this led to serious difficulties in finding staff that, in turn, led to attempts, often with little success, to recruit overseas workers.

In the late 1960s when bus workers took strike action they found that LT, with the tactic support of a Labour government, which as part of its prices and incomes policy was seeking to restrict pay increases, was only prepared to slightly increase pay and even then only in return for increased productivity levels. One Man Operated buses were introduced but did little to solve the staff shortage.

Bus passenger numbers continued to fall until the Tories were defeated in May 1981 in the elections to the Greater London Council (GLC), which had taken over control of LT on 1 January 1970.

The new Labour administration was prepared to allocate more funds for buses. Staff recruitment, was increased, planned service cuts were scrapped and fares were reduced by 32 percent on 4 October 1981. Passenger-demand rose by 10 per cent, it was the first time in two decades that the steady decline was halted and reversed.

This was all too much for the Tories and Tory-led Bromley Council was able to persuade the Law Lords that the GLC’s increased subsidy to LT was unlawful. On 10 March 1982, buses and tubes struck together for the first time ever. There were numerous public meetings across the capital at which community groups and LT workers organised a political campaign in defence of the GLC’s actions. The Tories responded by removing LT from GLC control and later established London Regional Transport whose board was packed with business people lacking any experience in running public transport systems. It was, as Fuller, stated ‘quite clear that LRT will be guided not by the needs of Londoners but by the requirements of the balance-sheet.’

The writer concluded this well-written and highly informative book by arguing that the TGWU London Bus Section needed to ‘link industrial militancy with a socialist political consciousness’ and that to safeguard their future ‘London Busworkers needed to engage in a political campaign to secure a say in they way their industry is planned and run, something which could feature as a component of an alternative economic strategy pursued by a socialist-orientated Labour government. ‘

To summarise, there are some important lessons in this book that current bus — and other — workers can learn from in order to play a role in advancing the whole working class movement.