The entrance to Jack Jones House, Liverpool is the location for a Liverpool City Council plaque dedicated to Merseysiders whose spirit of international solidarity saw them risk their lives in the fight against apartheid in South Africa. Internal resistance there in the forms of strikes, demonstrations and acts of sabotage encouraged international solidarity.

Seafarers and dockers have long been the most successful at organising international solidarity. Gerry Wan, deceased, was a black Liverpool-born seaman who was a chef on the Union Castle Line that sailed to South Africa.

According to Roger O’Hara, the Merseyside Area Secretary for the Communist Party (CP) of Great Britain in 1970, Wan delivered post, propaganda literature and parcels of money to places in Durban. These materials were hidden within ships’ cargo holds before departing from Britain.

Another CP member George Cartwright, deceased, was charged with collecting a crew together to navigate a yacht, the Avventura, from Somalia to close to the coast of South Africa where 19 ANC guerrilla fighters, fresh from training in the Soviet Union, arms and ammunition would come in on two dinghies. Seagoing engineer, Pat Newman, deceased, was one of those who agreed to join the mission. Ex-seaman, Eric Caddick, formerly a professional boxer, was another. He was a local black member of the CP. His father was from Barbados and his mother was from Liverpool.

Alex Moumbaris, who on a later mission was caught and sentenced to prison for twelve years, for which he served 7.5 as he escaped (1), was in charge of the landing with Bob Newland whilst there was an alternative beach where Bill McCaig and Daniel Ahern were waiting in case something unforeseen happened. In the years leading up to the proposed landing, Ahern and McCaig had worked clandestinely in South Africa on surveying beaches that were suitable for the operation.

Unfortunately, just off the coast of Kenya, the yacht, which had broken down on its initial journey, developed faults in the cooling system and a lack of spare bearings meant the mission had to be eventually aborted. Sadly, later attempts to get the young men over land into South Africa saw them captured and shot by the security forces.

McCaig had earlier been involved in propaganda work in South Africa in which he had distributed booklets around cargo holds for South African dockworkers to pick up when they unloaded ships.

Bill McCaig

He was given similar material to be posted within South Africa when he sailed there as a merchant seaman for the Union Castle Line. Later he worked permanently on Durban’s docks where he constantly moved around to try and spot opportunities for bringing in people without the port authorities knowing. He later had to leave South Africa quickly when it became apparent the South African police had become aware he was part of an underground network.

McCaig details his work in South Africa in an excellent book LONDON RECRUITS – The Secret War against Apartheid. This tells the story of a small unit of white anti-racist activists operating out of London that assisted the liberation movement, which found it very difficult to escape police surveillance after the Rivonia trial of Nelson Mandela and other leaders in 1963-64, to rebuild its capacity inside South Africa.

Moving in and out of South Africa, the recruits began by circulating banned literature through the postal system. They then become more audacious by showering leaflets from city rooftops and unfurling ANC banners and later they employed firework-type ‘bucket bombs’ for discharging leaflets at busy public venues whilst simultaneously blaring out tape-recorded speeches from such as Nelson Mandela.

Security police were baffled that an organisation they had virtually destroyed had quickly regained its capacity to act whilst the subversive activities inspired the oppressed with many young guerrilla combatants later recalling that the first time they had encountered an ANC message was through such propaganda coups.

Fortunately the vast majority of London recruits were not caught by the South African Authorities, as the penalties were severe if you were. After a series of successful operations, Sean Hosey was caught in 1971 taking passbooks and money to South African comrades in Durban. He received a physical battering and had to endure solitary confinement and interrogation before he received the mandatory five years in prison for breaching the Terrorism Act that was an effective catchall for anything that threatened white supremacy. Hosey was in Liverpool when the Liverpool City Council plaque to the five Merseyside men was unveiled on Friday 30 January 2015.

Their actions were praised by Obed Mlaba, the South African High Commissioner and ANC member: “We will never forget the overseas friends of our struggle. We thank them for the wonderful, vital job they did during the hard times we experienced. We look forward to working to continuing to work with British trade unionists.”

Liverpool-born Unite general secretary Len McCluskey said; “I was an anti-apartheid movement member. All praise for the comrades who risked their lives supporting our ANC members. It is appropriate that the plaque is mounted alongside the one bearing the names of Merseysiders who sacrificed their lives fighting for democracy in Spain in the 1930s. Both are great examples of international solidarity.”

1. Inside Out – Escape from Pretoria Prison by Tim Jenkin (Jakana Education, South Africa, 2003) and also at http://www.anc.org.za/books/escape0.html

London Recruits – the secret war against apartheid is published by Merlin Press at £15.99 post free. www.merlinpress.co.uk

In what was probably the first strike that can be truly called general, the 1842 General Strike involved nearly half a million workers. Coming at the peak of the Chartist campaign for basic democratic rights it combined resistance to wage-cuts in the coal, cotton and engineering industries with an all-out struggle for universals suffrage.

In what was probably the first strike that can be truly called general, the 1842 General Strike involved nearly half a million workers. Coming at the peak of the Chartist campaign for basic democratic rights it combined resistance to wage-cuts in the coal, cotton and engineering industries with an all-out struggle for universals suffrage.

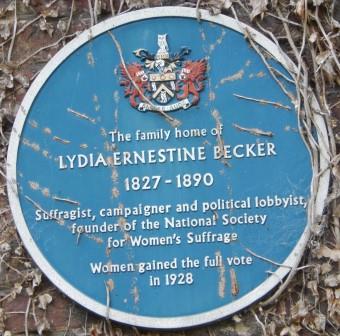

The Lydia Becker blue plaque was unveiled at her family home of Foxdenton Hall, Foxdenton Park on 28 September 1999. She was born in 1827 and was the eldest of 15 children. After hearing Barbara Bodichon lecture on women’s suffrage at a meeting in Manchester in 1866 she became converted to the idea that women should have the vote and spent the rest of her life campaigning on the issue.

The Lydia Becker blue plaque was unveiled at her family home of Foxdenton Hall, Foxdenton Park on 28 September 1999. She was born in 1827 and was the eldest of 15 children. After hearing Barbara Bodichon lecture on women’s suffrage at a meeting in Manchester in 1866 she became converted to the idea that women should have the vote and spent the rest of her life campaigning on the issue.

nn, a religious person throughout his life, was strongly opposed to workers slaughtering each other during the First World War. He was a firm supporter of the Bolshevik revolution in Russia in 1917 when for a brief period the working class took control of its own destiny. He retired from full-time employment in 1921, but remained actively involved for many years afterwards and he was sent to prison in 1932 after he criticised cuts in poor relief during a speech he made in Belfast.

nn, a religious person throughout his life, was strongly opposed to workers slaughtering each other during the First World War. He was a firm supporter of the Bolshevik revolution in Russia in 1917 when for a brief period the working class took control of its own destiny. He retired from full-time employment in 1921, but remained actively involved for many years afterwards and he was sent to prison in 1932 after he criticised cuts in poor relief during a speech he made in Belfast.